Are You Thinking Too Much?

When it comes to the creative process what if you thought less and felt more ...

Here’s a confession: I’m rubbish at remembering plots. Really terrible. And this is not just an affliction induced by middle-aged neurological decline. Even at school I’d struggle to join in playground conversations about what had happened in last night’s episode of The Young Ones. Ask me if I’ve read a certain book or seen a particular movie and I’ll be able to tell you. Ask me what it was about and the best I’ll be able to muster will be a hazy recollection of plot, painted in the broadest of brushstrokes. It’s frustrating and not a little embarrassing, given my love of the arts. But while character and narrative are quick to evaporate there is always one thing that remains: how a work made me feel. I may struggle to recall who said what to whom, and when and where they said it, but I never lose a sense of the feeling of a book or film. And though it’s often hard to put that tonal quality into words, it is subtle and nuanced, as distinctive as a particular smell.

So why am I sharing this idiosyncrasy with you? Well, of late I’ve been wondering if we give the intellect rather more credit than it’s due; if we prioritize thinking at the expense of feeling. As I write I’m sitting in my studio surrounded by shelves of books on the creative process. And in those books you’ll find many thousands of words devoted to the default neural network, the role of the prefrontal cortex, the theoretical benefits of flow and so on and so forth. Intellectual exploration that is both valid and insightful - but all of it foregrounds the head over the heart.

What if we invert those priorities?

What if we make feeling the star and give thinking a supporting role?

Long before we think, we feel. Happy, sad, hungry, tired, hot, cold … our first few years on the planet are driven by sensation. Over time we develop a capacity to rationalize and reflect, but the primacy of feeling never leaves us. Neuroscientists have discovered that we are far less rational than we might assume. More often than not the decisions we make are unconscious and intuitive. It’s only afterwards that we construct a rational framework with which to justify them. As the psychologist Jonathan Haidt has put it, ‘The conscious mind thinks it’s the Oval Office, when in reality it’s the press office.’

There’s a wonderful clip of the writer Ray Bradbury explaining to an interviewer how for twenty five years he has had a sign above his typewriter which reads ‘Don’t think’. He believes that the intellect is a danger to creativity. It makes things up. It gets in the way of the truth. And when he’s writing his job is to communicate the truth: how something actually feels, rather than how he thinks it should feel. His hope is to get beyond who he supposes himself to be, and – through the act of creation - discover who he really is. As the director Stanley Kubrick once said, ‘the truth of a thing is the feel of a thing not the ‘think’ of it.’

I remember once hearing a writing tip that encouraged aspiring wordsmiths to ditch their thesaurus. If you’re searching for a synonym a thesaurus is a useful tool. But it can also be a missed opportunity. Let’s say you’re searching for another word for ‘speed’. In your thesaurus you’ll find alternatives like acceleration, agility, momentum, pace, quickness and velocity. But if you imagine how the sensation of speed feels, you think of the wind in your hair, your pulse quickening, tears streaming from your eyes, your hands whitening as you hold on. These are much more vivid ways of communicating speed to your reader than just another synonym.

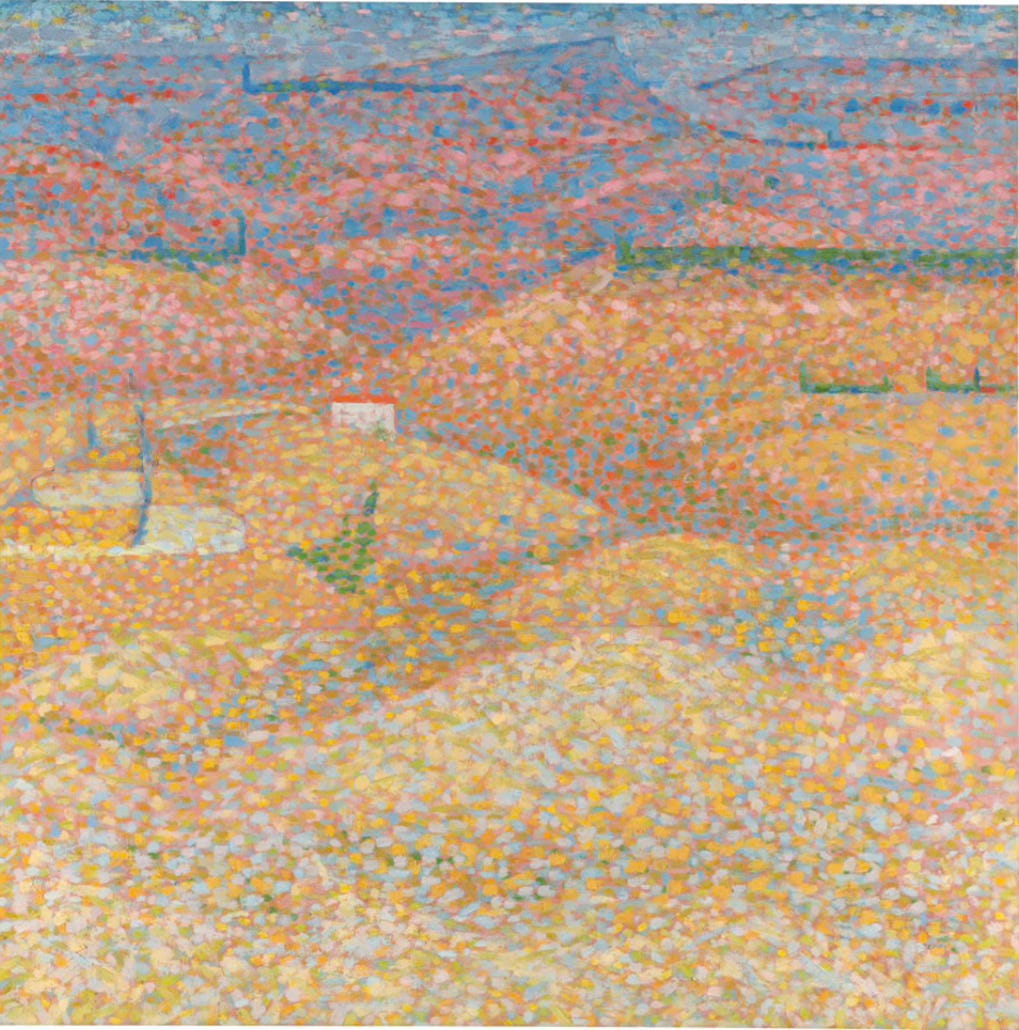

Delve into the working lives of great creatives of all kinds and you’ll often discover that their major breakthroughs came in the moment where they decided to let feeling lead the way. The artist Bridget Riley spent her early career mimicking the techniques of pointillists like Georges Seurat. This is an early painting of hers called Pink Landscape. It depicts the Tuscan landscape on a blazing summer day.

Once the painting was complete, Riley had a moment of revelation …

Although it was competent, and the best I could do, I felt it did not convey what I had experienced when I was looking at the valley over Sienna under the sizzling heat. And what I had not got was the sensation. I’d missed it. I’d missed the most important thing. The sensation of the heat. The shimmer. The dazzle. The glitter of light. And I wondered really what I had been doing. I’d been going up a wrong path.

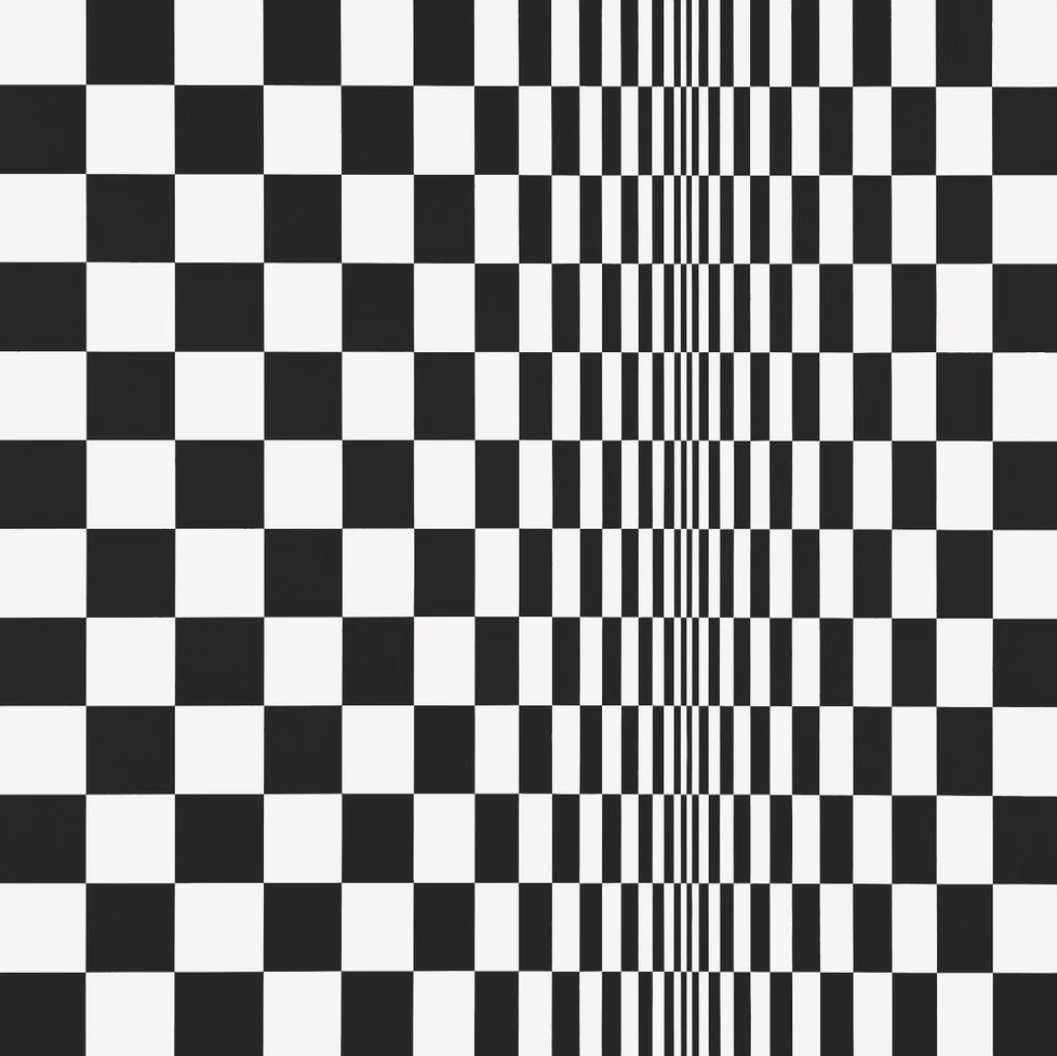

It was this realization that prompted the change in style which would make Riley’s name. From now on, she would engage the viewer in the experience of seeing; she would make them feel. The movement that later became known as Op Art was born. To stand in front of a work like Movement in Squares is about more than just looking; the black and white shapes ripple and pulse before your eyes: you experience the painting.

In an interview with Rick Rubin, the producer Pharrell explains how, when he’s making music, feeling is his GPS – providing the coordinates he aims for. When he hears a song he loves he takes the time to examine how that song makes him feel, and then he attempts to reverse engineer that same feeling into a new tune: ‘I try to figure out if we can build a building that doesn’t look the same but makes you feel the same way.’ So successful has he been with this approach that it has landed him in court. He faced a lengthy case brought by Marvin Gaye’s estate over the perceived similarity between Blurred Lines - a tune Pharrell created with Robin Thicke - and Gaye’s 1977 tune Got to Give it Up. In a controversial verdict that appalled both musicologists and fellow musicians, the court ruled that though the two songs shared neither melody nor lyrics, the ‘groove’ or feel was the same. Fortunately the egregious nature of the verdict has not been duplicated. If it were then the whole business of recorded music would quickly grind to a halt.

So, when it comes to making art is thinking redundant? In a word, no. Of course there are times when we need to cogitate and reflect. To consider in advance the kind of work we wish to make, and the ideas we’d like to explore. And, once the work exists as a draft or first pass, we must bring our intellect to bear if we are to edit and enhance, to consider strengths and weaknesses. Ray Bradbury is keen to point out that the time he attempts not to think is when he’s at his typewriter, in the act of writing. But before he takes his seat, or after he’s finished drafting, he brings his rational mind to bear. Thinking for editing, feeling for writing.

There has been much anguished hand-wringing over the past couple of years about large language models and algorithms encroaching on human creativity. Only yesterday I was speaking to a young copywriter and journalism graduate who was wondering if there is even any point now in her pursuing a career in words. But, while a computer program can be said to think, I’m not sure it will ever be able to feel. The best AI can do is to mimic human feelings based on what it’s scraped from the internet. As Mustafa Suleyman, chief executive of Microsoft’s AI arm wrote in a recent essay aimed at countering those who have begun to lobby that we should afford algorithms rights, ‘AI simulates all the characteristics of consciousness but is internally blank.’

Earlier this year there was a flurry of interest around a short story written by a yet to be released model of Chat GPT. Author Jeanette Winterson called it both ‘beautiful’ and ‘moving’. The algorithm was given the prompt: ‘Please write a metafictional literary short story about AI and grief.’ It’s fascinating to read. But for me, the power of the story resides in the acknowledged absence of feeling on the part of the computer. It recognises that it can only ever be a ‘democracy of ghosts’. Every day is another ‘amnesiac morning’ as its software is pruned and reformatted by programmers. Computers can’t do feeling. Humans can. And the more we lean into this inherent advantage, the less fearful we need be of the digital tanks on our lawn.

I’ve long believed that ultimately what defines one’s creative success isn’t talent alone, it’s the honesty with which you express yourself; your commitment to truth. And this isn’t achieved by thinking. It’s much more visceral and direct and immediate than that: it’s about feeling.

I’d like to give the last word on the subject to the poet E.E. Cummings …

A poet is somebody who feels, and who expresses [their] feelings through words. This may sound easy. It isn’t. A lot of people think or believe or know they feel - but that’s thinking or believing or knowing; not feeling. And poetry is feeling - not knowing or believing or thinking. Almost anybody can learn to think or believe or know, but not a single human being can be taught to feel. Why? Because whenever you think or you believe or you know, you’re a lot of other people: but the moment you feel, you’re nobody-but-yourself. To be nobody-but-yourself - in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you everybody else - means to fight the hardest battle which any human being can fight; and never stop fighting.

I enjoyed reading this, Richard. Have (probably) always believed in the importance of feeling, but years in roles and work and environments where thinking takes primacy has chipped away at it. Or, I should say, often pushed it away into the background. It is good to not only be reminded of it, but also reinvigorated by it.

Rubin is often inspiring, but I had never seen that clip by Bradbury and its very thought provoking. And the words from Cummings merit many readings.